Debt Collection Agency in Philippines - No Win, No Fee

Your claims are handled exclusively by Upper Class Collections, our licensed debt collection partner with 19+ years of expertise and offices across 8 countries including Cebu City.

Why Debitura is the Smart Choice for Debt Collection in the Philippines

Fast, Simple & Risk-Free Debt Collection in the Philippines

Debitura is a global, tech-enabled collections platform working with locally registered agencies and law firms in 183 countries. In the Philippines, your case is handled by UPPER CLASS COLLECTIONS CORPORATION, an SEC-registered collection agency based in Cebu City.

- Risk-free pricing: No fees unless we recover.

- Quick setup: Submit invoices in a few clicks.

- Real-time tracking: Live status, actions, and payments in one portal.

- Compliance: Aligned with the Financial Products & Services Consumer Protection Act (RA 11765), SEC MC 18-2019, BSP collection standards & the Data Privacy Act

Start recovering your Philippine claims in 2 minutes

- Submit your claim: Upload your unpaid claim in minutes via the dashboard, REST API, or plug-and-play ERP integrations like Xero or local systems such as QNE.

- Local collection begins: We assign the case to UPPER CLASS COLLECTIONS CORPORATION, who contacts the debtor in Filipino or English within 24 hours.

- Get paid: Funds are remitted on recovery. If court action is required, you choose from 1–3 fixed-price legal quotes before anything proceeds—for example, a small claims case (for eligible amounts) or a civil action for sum of money.

Transparent Pricing for Debt Collection in the Philippines

With Debitura, you only pay when we succeed. In the Philippines, fees are invoiced locally by UPPER CLASS COLLECTIONS CORPORATION in Philippine pesos (PHP), with any applicable Value-Added Tax (VAT).

- No win, no fee: Pre-legal collection in the Philippines is success-based — no setup costs or subscriptions.

- Local, transparent invoicing: Recovered proceeds are remitted, and the success fee is deducted directly by UPPER CLASS COLLECTIONS CORPORATION.

- No hidden charges: Same clear, global terms apply everywhere.

- Legal action is optional: You review and approve fixed-price quotes before any legal step is taken.

Fast, Simple & Risk-Free Debt Collection in the Philippines

Debitura is a global, tech-enabled collections platform working with locally registered agencies and law firms in 183 countries. In the Philippines, your case is handled by UPPER CLASS COLLECTIONS CORPORATION, an SEC-registered collection agency based in Cebu City.

- Risk-free pricing: No fees unless we recover.

- Quick setup: Submit invoices in a few clicks.

- Real-time tracking: Live status, actions, and payments in one portal.

- Compliance: Aligned with the Financial Products & Services Consumer Protection Act (RA 11765), SEC MC 18-2019, BSP collection standards & the Data Privacy Act

Debt Collection in the Philippines: Your Complete 2026 Guide

Why you can trust this guide

At Debitura, we uphold the highest standards of impartiality and precision to bring you comprehensive guides on international debt collection. Our editorial team boasts over a decade of specialized experience in this domain.

Questions or feedback? Email us at contact@debitura.com — we update this guide based on your input.

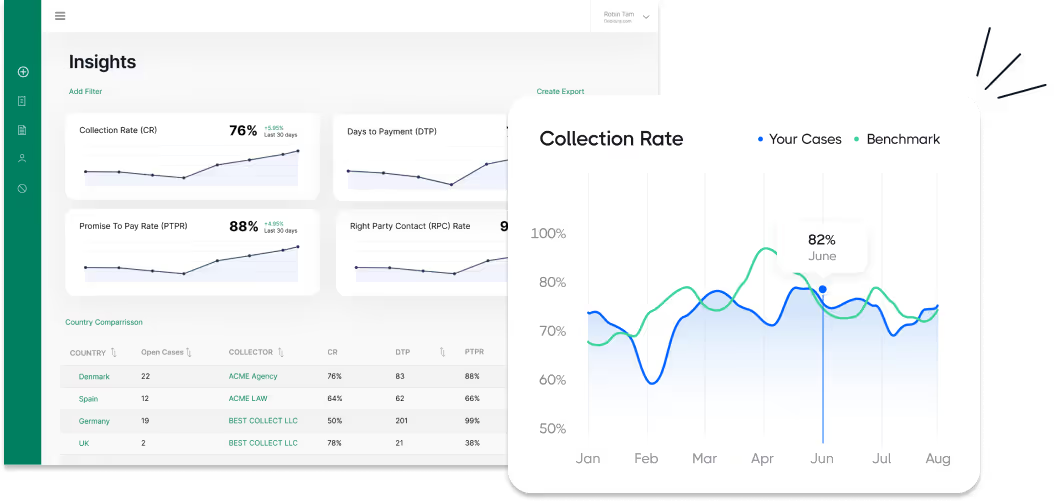

Debitura By the Numbers:

- 10+ years focused on international debt collection

- 100+ local attorneys in our partner network

- $100M+ recovered for clients in the last 18 months

- 4.9/5 average rating from 621 reviews

Expert-led, locally validated

Written by Robin Tam (16 years in global B2B debt recovery). Every page is reviewed by top local attorneys to ensure legal accuracy and practical steps you can use.

Contributing local experts:

Last updated:

Use this guide to navigate debt recovery in the Philippines. Written by the Debitura team in collaboration with local debt collection agencies and lawyers.

It distills the legal framework, costs, timelines, limitation rules, and enforcement tools. You also get step-by-step workflows, mini-tables, and checklists—grounded in the Civil Code (RA 386) and the ₱2,000,000 Small Claims expansion.

What we will cover:

Essential Facts for debt recovery in the Philippines

Before we dive into the details of debt recovery in the Philippines, here are quick answers to the questions we hear most from international creditors. Costs, timelines, limitation and interest rules, and the documents you need. All at a glance.

How much does debt collection cost in the Philippines?

Pre-legal collection often runs on “no cure, no pay.” Suing adds filing fees under Rule 141 and, outside Small Claims, lawyer’s fees. If you win, execution adds sheriff/execution fees that can be charged to the debtor upon recovery.

How long does debt collection take in the Philippines?

Expect 2–3 months for pre-legal efforts. Small Claims is designed to conclude roughly within 1–3 months from summons. Ordinary civil suits often take 12–24 months to judgment; enforcement then varies by assets available.

What are the limitation periods and interest rules in the Philippines?

Claims on written contracts prescribe in 10 years (6 years if purely oral). Written demand or acknowledgment interrupts and resets the clock. If no contractual rate applies, legal interest is 6% per annum; money judgments earn 6% from finality.

What documents do I need to collect a debt in the Philippines?

Gather the contract or promissory note, invoices and signed delivery/acceptance, a statement of account, and a final demand with proof of service. Corporate claimants should add an SPA or secretary’s certificate authorizing filing/appearance.

- Contract/promissory note: Proves obligation and agreed charges.

- Invoices + signed delivery/acceptance: Proves performance and receipt.

- Statement of account/computation: Shows principal, interest, penalties.

- Demand letter + proof of service: Supports default and interrupts prescription.

- SPA/Secretary’s certificate (companies): Authorizes filing/representation.

How does the debt collection process work in the Philippines?

In the Philippines, your path turns on two questions: is the claim disputed, and do you already hold a legal title. If there is no dispute and you have no title, begin with amicable steps like reminders, a formal demand, and a short payment plan. If the claim is disputed, you must file in court to settle liability. A legal title is the court’s official decision that the debtor owes you money. This is usually a final judgment in Small Claims or an ordinary civil case, or a judgment upon compromise that approves your settlement. With a title, you can ask for a writ of execution and court sheriffs can garnish accounts or levy assets under Rule 39.

Is the claim time-barred?

- Philippine “prescription” rules set hard deadlines. Written contracts prescribe in 10 years. Oral contracts in 6 years. Written demand or acknowledgment interrupts and resets the clock.

- If prescription has run, the debtor can plead it and the court will dismiss. If still within time, proceed.

Is the claim disputed?

- If undisputed, try amicable steps first. Use reminders, a formal demand, and a short payment plan. If unpaid, file a Small Claims case or an ordinary suit.

- If disputed, file promptly in the competent court. Do not linger in pre-legal once liability is contested.

Do you have a legal title?

- A legal title is a court-issued basis to enforce. It is the official recognition that money is owed.

- What qualifies: a Small Claims or ordinary civil judgment, or a court-approved compromise judgment.

- If you already have a title, apply for a writ of execution and instruct the court sheriff to garnish or levy under Rule 39.

Who Does What in the Philippines Debt Collection

In the Philippines, agencies handle amicable recovery, lawyers run court proceedings, and court sheriffs enforce judgments. Choose by dispute status, claim size, and stage. Enforcement needs a legal title such as a judgment or approved compromise and proceeds under Rule 39 with sheriff-led garnishment or levy.

Debt Collection Agencies in the Philippines

- Best for: Early, undisputed debts and payment plans.

- What they do: Reminders, demand letters, negotiate settlements, payment links.

- Compliance: Follow FCPA and BSP or SEC rules. Respect 8am–9pm contact hours. No harassment or third-party disclosure.

- Typical fees / terms: Contingency commission on recoveries. Often no cure, no fee. Client usually absorbs the fee.

- Escalate when: No response after final demand or debtor disputes liability. File Small Claims or an ordinary suit.

Debt-Collection Lawyers in the Philippines

- Best for: Disputed claims, complex cases, or amounts above Small Claims.

- What they do: Draft demands, file and prosecute cases, obtain judgments or court-approved settlements. Advise on enforcement strategy.

- Compliance: Follow Rules of Court and professional responsibility. In Small Claims, lawyers cannot appear at the hearing.

- Typical fees / terms: Contingency or fixed fees. Attorney’s fees may be awarded if allowed by contract or law and moderated by the court.

- Engage when: The debtor contests liability, cross-border issues arise, or you need to fast-track to a legal title.

Court Sheriffs in the Philippines

- Best for: Post-judgment recovery once a legal title exists.

- What they do: Execute writs. Garnish bank accounts and wages. Levy and auction non-exempt property per Rule 39.

- Compliance: Observe exemptions, notice and sale rules, and sheriff conduct guidelines. Court supervision applies.

- Typical fees / terms: Execution fee and sheriff commission on realized amounts. Costs are added to the debtor on recovery.

- Instruct when: Judgment is final and debtor has assets to garnish or levy. Provide asset leads to the sheriff.

Which laws and courts apply to debt collection in the Philippines?

In the Philippines, the core rules are the Civil Code on obligations, the Supreme Court’s Rules of Court, and the Small Claims framework under A.M. No. 08-8-7-SC. These govern how creditors, agencies, and lawyers recover debts. The system is largely codified, with case law guiding application across first-level and regional trial courts. Conduct and data use follow the Data Privacy Act.

Civil court system in the Philippines

- Use when: Selecting the forum and appeals path.

- Levels: First-level courts hear Small Claims up to ₱2,000,000. Ordinary actions above that are filed per jurisdictional rules, typically in the Regional Trial Court. Appeals go to the RTC or Court of Appeals, then exceptionally the Supreme Court.

- Filing basics: Pleadings, service, and deadlines follow the Rules of Court.

- Service: Local service per the Rules; cross-border service available via the Hague Service Convention (PH acceded in 2020).

- Outcome: Judgment or order that enables enforcement.

- Creditor must: File in the competent court and observe time limits.

Key legislation in the Philippines

- Key legislation: Civil Code on obligations and prescription; Rules of Court for procedure and enforcement (Rule 39); Small Claims Rules under A.M. 08-8-7-SC; Financial Rehabilitation and Insolvency Act; sector conduct rules from BSP and SEC.

- Practical effect: Defines default and recoverable costs, filing and service steps, writs and sheriff powers, and stays or priority in insolvency.

- Recognition: Foreign money judgments are enforced via an independent action; foreign arbitral awards recognized under the New York Convention and ADR Act.

- Creditor must: Cite the correct article or rule and keep evidence ready.

- As of: March 2025.

Consumer and data protection in the Philippines

- Applies to: All pre-legal outreach and case handling.

- You must: Follow Data Privacy Act principles of lawful basis, minimization, and security.

- You should not: Harass, mislead, or disclose excessive data; regulators prohibit abusive tactics.

- Comms basics: State accurate amounts, set clear deadlines, and honor opt-out requests.

- Special rules: For banks and lending apps, observe BSP and SEC collection guidelines, including restricted contact hours and no public shaming.

- Creditor must: Retain evidence proportionately and set retention limits consistent with privacy rules.

How does amicable (pre-legal) debt collection work in the Philippines?

Amicable collection resolves unpaid invoices without court by using reminders, a final demand, and negotiation. Aim for full payment or a written acknowledgment with an instalment plan. Use multi-channel outreach, clear deadlines, demand letters, and keep every exchange documented. Written demand also interrupts prescription and resets the clock.

- Case criteria: Undisputed and within time limits.

- Statute of limitations: 10 years written, 6 years oral; written demand or acknowledgment interrupts.

- Goal: Full payment or signed plan with acknowledgment of debt.

- Typical timeframe: About 30–90 days.

- Key actors involved: Collection agency, creditor’s AR team, or lawyer for demand letter.

- Typical cost for the creditor: “No cure, no pay” success fee from recoveries; optional fixed fee for a lawyer’s demand.

- Typical cost for the debtor: Contract interest or, if none, 6% per annum legal interest from default; reasonable admin fees if allowed by contract.

- Escalate when: Final demand lapses, claim is disputed, limitation risk arises, or asset dissipation is suspected.

How does the pre-legal timeline run in the Philippines?

Use the cadence below and adjust deadlines to your case.

What costs apply in the amicable phase?

Debtors usually bear contract or statutory interest and agreed charges. Creditors commonly engage agencies on a no cure, no pay basis.

When to Escalate to Court in the Philippines

- Escalation triggers: Missed final demand, disputed liability, looming prescription, suspected asset transfer.

- Prepare next: Evidence bundle, statement of account, interest and costs computation, proof of demand.

- Hand-off: Agency or creditor instructs a lawyer to file in the proper court.

Use the Courts to Obtain an Enforceable Title in the Philippines

File a case when the claim is disputed or amicable steps fail. The goal is a court-issued legal title (judgment or approved compromise) that stops prescription and can be enforced by writ of execution. Small Claims (first-level courts) is the fast track for money claims up to ₱2,000,000; ordinary actions follow the Rules of Court (sc.judiciary.gov.ph).

- Goal: Obtain an enforceable court title to enable execution.

- Typical timeframe: Small Claims about 1–3 months to judgment; ordinary suits often 12–24 months.

- Key actors involved: Creditor, court (MTC/MeTC or RTC), judge, and court sheriff at enforcement.

- Typical cost for the creditor: Filing and service fees under Rule 141, plus representation costs in ordinary suits.

- Typical cost for the debtor: Principal, contractual or legal interest, costs of suit, and court-awarded attorney’s fees if allowed.

- Result: Judgment or consent judgment that interrupts prescription and allows Rule 39 execution.

What is the cost of legal action in the Philippines?

You’ll shoulder the upfront costs: court filing fees, service (and any translation), plus lawyer’s fees for ordinary cases. If you win, standard “costs of suit” are typically charged to the losing party; attorney’s fees are awarded only if your contract provides for them or the Civil Code allows it. The debtor can be ordered to pay the principal, interest, and court-awarded costs.

How do I determine the appropriate court in the Philippines?

Use the Small Claims track in the first-level courts (Metropolitan/Municipal Trial Courts) for money claims up to ₱2,000,000 under the Supreme Court’s Small Claims rules. Above that, file an ordinary civil case in the Regional Trial Court; appeals go to the Court of Appeals (and, on pure questions of law, the Supreme Court). Pick venue by claim value, subject matter, and any valid venue/jurisdiction clause. Serve documents under the Rules of Court for domestic service; for cross-border service, use the Hague Service Convention per the Supreme Court’s implementing order. File within the limitation period, attach your evidence bundle, and follow the Rules of Court.

Fast-Track Option in the Philippines

- Name: Small Claims (Rules on Expedited Procedures in the First-Level Courts, A.M. No. 08-8-7-SC). sc.judiciary.gov.ph

- Best for: Uncontested or simple money claims within ₱2,000,000.

- What it does: Provides a quick money judgment without lawyer appearances at the hearing.

- Key steps: File Statement of Claim with exhibits → court issues summons and sets hearing within about 30 days → mediation then one-day hearing → decision typically same day or within 24 hours. sc.judiciary.gov.ph

- Objection result: Complex or inappropriate matters proceed under the ordinary track.

- Typical duration: Roughly 1–3 months to final judgment; judgments are immediately final and executory as provided by the rules.

- Filing basics: Use Supreme Court forms, pay filing fees under Rule 141.

Ordinary Proceedings in the Philippines

- Best for: Disputed, complex, or higher-value claims.

- Key steps: Complaint and evidence → summons and Answer → pre-trial and mediation → trial on judicial affidavits and cross-examination → judgment.

- Evidence focus: Contract or note, invoices and delivery receipts, statement of account, and proof of demand.

- Typical duration: Often 12–24 months at trial level, longer with appeals.

- Outcome: Money judgment or compromise judgment; appeal path per the Rules of Court.

- Cost shifting: Costs of suit to losing party; attorney’s fees only if contract or Civil Code grounds justify an award.

How does debt enforcement work in the Philippines?

A creditor can enforce only with a legal title such as a court judgment or a court-approved compromise. Enforcement is carried out by court sheriffs under Rule 39 using a writ of execution, garnishment, and levy and sale. Choose tools based on known assets and proportionality, and follow the Rules of Court.

- Goal: Recover sums via court-authorized measures using a valid title.

- Actors: Court sheriffs, creditor, debtor, and third parties like banks or employers.

- Prerequisite: Legal title required; confirm proper service and timelines.

- Typical timeframe: Weeks to months; speed depends on available assets.

- Costs: Execution and sheriff fees paid upfront by the creditor; standard costs may be shifted to the losing party.

- Limits: Exempt items and protected income apply; salaries can be garnished subject to law.

What are the ways to enforce a claim in the Philippines?

Enforcement options depend on what assets you can identify. The court issues a writ, sheriffs act, and third parties must comply. Start with the assets easiest to reach, keep actions proportionate, and document each step under Rule 39.

- Seizure of movables: Instruct the sheriff to inventory, seize, and auction personal assets under a writ of execution.

- Bank account attachment: Seek garnishment to freeze and turn over deposits by serving the bank.

- Wage garnishment: Serve the employer to garnish salaries while observing statutory protections.

- Real-property measures: Levy registered property and conduct a sheriff’s sale with required notices.

- Third-party debt order: Garnish receivables owed to the debtor by customers or platforms.

- Information measures: Request court-directed disclosures or registry searches to locate assets.

- Voluntary compliance tools: Offer payment plans or submit a consent judgment to avoid intrusive measures.

What is the debt enforcement process in the Philippines?

Begin only once your title is final and executable. Pick remedies that match known assets, file for a writ, let the sheriff execute, and account for proceeds. If nothing is found, gather new intel or consider insolvency options.

- Check readiness: Title is final; interest and costs updated; debtor details confirmed.

- Choose remedy: Match assets to tool such as bank, wages, movables, property, or receivables.

- File and serve: Move for a writ of execution with the court; pay execution fees; arrange service on debtor and garnishees.

- Execution phase: Sheriff performs garnishment or levy; banks and employers comply as required.

- Proceeds and accounting: Apply proceeds to principal, interest, and lawful costs; return any surplus per the Rules.

- If empty-handed: Seek information orders or registry checks, retry with new intelligence, or evaluate insolvency.

- Closure and monitoring: Remember Rule 39 timing rules for execution and calendar re-attempts if the debtor’s situation improves.

How do insolvency procedures work in the Philippines?

Once a case opens, a court stay halts individual suits and executions under the Financial Rehabilitation and Insolvency Act (FRIA). Creditors must file a proof of claim by the court-set deadline to share in distributions. Results depend on rehabilitation or liquidation, and the priority waterfall set by statute.

- Goal: Maximize recovery through a supervised, collective process.

- Typical timeframe: Months to years, depending on plan approval or winding up.

- Key actors involved: Court, rehabilitation receiver or liquidator, creditors meeting or committee.

- Typical cost for the creditor: Claim filing and document prep, translations if needed, counsel time.

- Typical cost for the debtor: Estate costs and administration expenses paid from estate assets.

- Effect on enforcement: Individual actions pause and you must proceed through the estate.

What types of insolvency exist in the Philippines, and what outcomes can creditors expect?

Liquidation sells assets and pays by statutory priority, so unsecured dividends are often modest. Rehabilitation restructures debts under a court approved plan, adjusting terms and timing. Individuals may seek suspension of payments or liquidation. FRIA also provides a framework for recognizing foreign proceedings by court action. Discharge or case closure depends on plan completion or the end of liquidation.

- Liquidation or bankruptcy: Court liquidation with asset sales; payments follow statutory priority. Unsecured dividends are usually low.

- Reorganization or restructuring: Court supervised rehabilitation with a plan. Contracts may be adjusted, assumed, or rejected.

- Pre pack or scheme: Pre negotiated rehabilitation may be filed for court approval to obtain the stay and plan confirmation.

- Personal vs corporate: Individuals use suspension of payments or liquidation. Corporations use rehabilitation or liquidation.

- Cross border recognition: Philippine courts may recognize foreign insolvency under FRIA cross border provisions.

- Discharge timeline and exclusions: Discharge arises on plan completion or liquidation close. Secured claims are satisfied from collateral first, and some obligations follow statutory treatment.

What is the insolvency process in the Philippines?

Verify the case details, stop solo enforcement, and file a complete claim on time. Engage in meetings, challenge rankings if needed, and track dividends under the priority rules until closure.

- Detect and verify: Confirm proceeding type, case number, court, and receiver or liquidator.

- Stop individual action: Obey the stay order. Withdraw or park executions and suits.

- File proof of claim: Use the court prescribed form. Attach contract, invoices, delivery proofs, statement of account, and interest or cost computations. Meet the court set deadline.

- Attend or monitor meetings: Join the creditors meeting, committee if constituted, and vote on the plan or liquidation steps.

- Challenge if needed: Contest claim amounts, rankings, preferences, or set offs using the court’s objection procedures.

- Track distributions: Expect dividends according to statutory priority. Monitor scheduled reports and payouts.

- After closure: Your local judgment remains enforceable for up to 10 years in line with execution timing rules. Consider post discharge options for debts not covered.

Find a Local Debt Collection Lawyer

Need court-ready representation? Share your case once and receive up to three proposals from vetted litigation attorneys—free, fast, and with no commitment.

- Verified specialists

- Quotes in 24 h, no hidden fees

- Fair, pre-negotiated rates

Narag Law Office is a premier law firm in Las Piñas offering effective Debt Collection services in the Philippines, established in 2015, renowned for producing bar topnotchers and trusted by over 20 companies for their professional and dedicated legal expertise.

AEDiaz Law Office is a premier law firm in Makati Metro Manila offering effective Debt Collection services in the Philippines, recognized for its expertise since 2008, and trusted for its commitment to excellence in legal practice and dispute resolution.

Bala & Bonilla Law Offices is a premier law firm in Quezon City offering effective Debt Collection services in the Philippines, positioning the firm as the go-to partner for debt recovery with expertise since 2022 and competitive pricing starting at USD 1,000.

Victoriano Tiu and Aureus is a premier law firm in Makati City offering effective Debt Collection services in the Philippines, established in 2020, and recognized for excellence with multiple awards and memberships.

Abanto Law Firm is a premier law firm in Pasig City offering effective Debt Collection services in the Philippines, positioning itself as the go-to partner for debt recovery with a foundation in 2022, strategic global partnerships, and memberships in prestigious legal organizations.

Pangan Law Office is a premier law firm in Alabang offering effective Debt Collection services in the Philippines, positioning the firm as the go-to partner for debt recovery with its 2023 founding, member of the Integrated Bar of the Philippines, and service in Australia.

Duran & Duran-Schulze Law is a premier law firm in Taguig offering effective Debt Collection services in the Philippines, established in 2013, recognized for its strategic legal expertise and trusted by businesses for reliable debt recovery solutions.

The Northern Star Consultancy Inc. is a premier debt recovery agency in San Rafael offering effective Debt Collection services in the Philippines, positioning itself as the go-to partner for debt recovery since 2025, with multiple awards and memberships enhancing its credibility.

.svg)

.webp)

.png)

.png)

.svg)

.svg)